This post is another addition to the best practices series available in this blog. In this post, we cover some well-known and little-known practices that we must consider while handling exceptions in our next java programming assignment.

1. Inbuilt Exceptions in Java

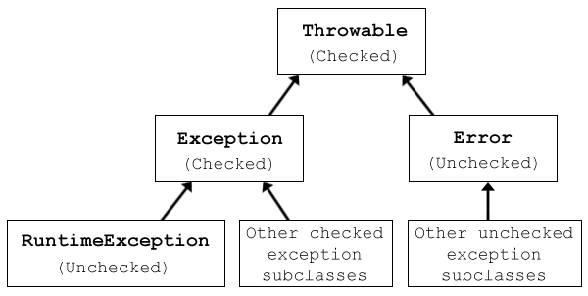

Before we dive into deep concepts of exception-handling best practices, let us start with one of the most important concepts which is to understand that there are three general types of throwable classes in Java.

1.1. Checked Exceptions

The checked exceptions must be declared in the throws clause of a method. They extend Exception class and are intended to be an “in your face” type of exceptions. Java wants us to handle them because they depend on external factors outside our program.

A checked exception indicates an expected problem that can occur during normal system operation. Mostly these exceptions happen when we try to use external systems over a network or read resources in the filesystem. Mostly, the correct response to a checked exception should be to try again later or to prompt the user to modify his input.

1.2. Unchecked Exceptions

The unchecked exceptions do not need to be declared in a throws clause. JVM simply doesn’t force us to handle them as they are mostly generated at runtime due to programmatic errors. They extend RuntimeException.

The most common example is a NullPointerException. An unchecked exception probably shouldn’t be retried, and the correct action should usually be to do nothing, and let it come out of your method and through the execution stack. At a high level of execution, this type of exception should be logged.

1.3. Errors

The errors are serious runtime environment problems that are almost certainly not recoverable. Some examples are OutOfMemoryError, LinkageError, and StackOverflowError. They generally crash your program or part of the program. Only a good logging practice will help you determine the exact causes of errors.

2. Custom Exceptions

Anytime when the user feels that he wants to use its own application-specific exception for some reason, he can create a new class extending the appropriate superclass (mostly its Exception) and start using it in appropriate places. These user-defined exceptions can be used in two ways:

- Either directly throw the custom exception when something goes wrong in the application.

throw new DaoObjectNotFoundException("Couldn't find dao with id " + id);- Or wrap the original exception inside the custom exception and throw it.

catch (NoSuchMethodException e) {

throw new DaoObjectNotFoundException("Couldn't find DAO with " + id, e);

}Wrapping an exception can provide extra information to the user by adding your own message/ context information, while still preserving the stack trace and message of the original exception. It also allows you to hide the implementation details of your code, which is the most important reason to wrap exceptions.

Now, let us start exploring the best practices followed for exception handling industry-wise.

3. Best Practices for Exception Handling

3.1. Never swallow the exception in the catch block

catch (NoSuchMethodException e) {

return null;

}Doing this not only returns “null” instead of handling or re-throwing the exception, it totally swallows the exception, losing the original cause of the error forever. And when you don’t know the reason for failure, how would you prevent it in the future? Never do this !!

3.2. Declare the specific checked exceptions that the method can throw

public void foo() throws Exception { //Incorrect way

}Always avoid doing this as in the above code sample. It simply defeats the whole purpose of having checked exceptions. Declare the specific checked exceptions that your method can throw.

If there are just too many such checked exceptions, you should probably wrap them in your own exception and add information in the exception message. You can also consider code refactoring also if possible.

public void foo() throws FileNotFoundException, ParseException { //Correct way

}3.3. Do not catch the Exception class rather catch specific subclasses

try {

someMethod();

} catch (Exception e) {

LOGGER.error("method has failed", e);

}The problem with catching the Exception class is that if the method later adds a new checked exception to its method signature, the developer’s intent is that you should handle the specific new exception. If your code just catches Exception (or Throwable), you’ll never know about the change and the fact that your code is now wrong and might break at any point of time in runtime.

3.4. Never catch Throwable

Well, it is one step more serious trouble. Because java errors are also subclasses of the Throwable.

Errors are irreversible conditions that can not be handled by JVM itself. And for some JVM implementations, JVM might not actually even invoke your catch clause on an Error.

3.5. Always correctly wrap the exceptions in custom exceptions so that the stack trace is not lost

catch (NoSuchMethodException e) {

throw new MyServiceException("Some information: " + e.getMessage()); //Incorrect way

}This destroys the stack trace of the original exception and is always wrong. The correct way of doing this is:

catch (NoSuchMethodException e) {

throw new MyServiceException("Some information: " , e); //Correct way

}3.6. Either log the exception or throw it but never do both

catch (NoSuchMethodException e) {

LOGGER.error("Some information", e);

throw e;

}As in the above example code, logging and throwing will result in multiple log messages in log files, for a single problem in the code, and makes life hell for the engineer who is trying to dig through the logs.

3.7. Never throw any exception from the finally block

try {

someMethod(); //Throws exceptionOne

} finally {

cleanUp(); //If finally also threw any exception the exceptionOne will be lost forever

}This is fine, as long as cleanUp() can never throw any exception. In the above example, if someMethod() throws an exception, and in the finally block also, cleanUp() throws an exception, that second exception will come out of the method and the original first exception (correct reason) will be lost forever.

If the code that you call in a finally block can possibly throw an exception, make sure that you either handle it or log it. Never let it come out of the finally block.

3.8. Always catch only those exceptions that you can handle

catch (NoSuchMethodException e) {

throw e; //Avoid this as it doesn't help anything

}Well, this is the most important concept. Don’t catch any exception just for the sake of catching it. Catch any exception only if you want to handle it or, if you want to provide additional contextual information in that exception.

If you can’t handle it in catch block, then the best advice is just don’t catch it only to re-throw it.

3.9. Don’t use printStackTrace() statement or similar methods

catch (SomeException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

throw e;

}Never leave printStackTrace() after finishing your code. Chances are one of your fellow colleagues will get one of those stack traces eventually and have exactly zero knowledge as to what to do with it because it will not have any contextual information appended to it.

3.10. Use finally blocks instead of catch blocks if you are not going to handle the exception

try {

someMethod(); //Method 2

} finally {

cleanUp(); //do cleanup here

}This is also a good practice. If inside your method you are accessing some method 2, and method 2 throw some exception which you do not want to handle in method 1, but still want some cleanup in case exception occurs, then do this cleanup in finally block. Do not use catch block.

3.11. Remember “Throw early Catch late” principle

This is probably the most famous principle about Exception handling. It basically says that you should throw an exception as soon as you can, and catch it as late as possible. You should wait until you have all the information to handle it properly.

This principle implicitly says that you will be more likely to throw it in the low-level methods, where you will check whether single values are null or not appropriate. And you will be making the exception to climb the stack trace for quite several levels until you reach a sufficient level of abstraction to be able to handle the problem.

3.12. Always clean up after handling the exception

If you are using resources like database connections or network connections, make sure you clean them up. If the API you are invoking uses only unchecked exceptions, you should still clean up resources after use, with try-finally blocks. Inside try block access the resource and inside finally close the resource. Even if any exception occurs in accessing the resource, then also resource will be closed gracefully.

As a best practice, use try-with-resources for AutoCloseable resources.

3.13. Throw only relevant exceptions from a method

Relevancy is important to keep the application clean. A method that tries to read a file; if throws NullPointerException then it will not give any relevant information to the user. Instead, it will be better if such an exception is wrapped inside a custom exception e.g. NoSuchFileFoundException then it will be more useful for users of that method.

3.14. Never use exceptions for flow control in your program

We have read it many times, but sometimes we see code in our project where the developer tries to use exceptions for application logic. Never do that. It makes code hard to read, understand and ugly.

3.15. Validate user input to catch adverse conditions very early in the request processing

Always validate user input in a very early stage, even before it reached the actual request handler. It will help you to minimize the exception-handling code in your core application logic. It also helps you make application-consistent if there is some error in user input.

For example: If in the user registration application, you are following the below logic:

- Validate the User

- Insert User

- Validate the Address

- Insert Address

- If there is a problem, then roll back everything.

This is a very incorrect approach. It can leave your database in an inconsistent state in various scenarios. Rather validate everything first and then take the user data in the dao layer and make DB updates.

The correct approach is:

- Validate the User

- Validate the Address

- Insert User

- Insert Address

- If there is a problem, then roll back everything.

3.16. Always include all information about an exception in the single log message

LOGGER.debug("Using cache sector A");

LOGGER.debug("Using retry sector B");Don’t do this.

Using a multi-line log message with multiple calls to LOGGER.debug() may look fine in your test case, but when it shows up in the log file of an app server with 400 threads running in parallel, all dumping information to the same log file, your two log messages may end up spaced out 1000 lines apart in the log file, even though they occur on subsequent lines in your code.

Do it like this:

LOGGER.debug("Using cache sector A, using retry sector B");3.17. Pass all relevant information to exceptions to make them informative as much as possible

This is also very important to make exception messages, and stack traces useful and informative.

What is the use of a log, if you cannot determine anything from it? These types of logs just exist in your code for decoration purposes.

3.18. Always terminate the thread which it is interrupted

while (true) {

try {

Thread.sleep(100000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {} //Don't do this

doSomethingCool();

}InterruptedException is a clue to your code that it should stop whatever it’s doing. Some common use cases for a thread getting interrupted are the active transaction timing out, or a thread pool getting shut down.

Instead of ignoring the InterruptedException, your code should do its best to finish up what it’s doing and finish the current thread of execution.

So to correct the example above:

while (true) {

try {

Thread.sleep(100000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

break;

}

}

doSomethingCool();3.19. Use template methods for repeated try-catch

There is no use in having a similar catch block in 100 places in your code. It increases code duplicity which does not help anything. Use template methods for such cases.

For example, below code tries to close a database connection.

class DBUtil{

public static void closeConnection(Connection conn){

try{

conn.close();

} catch(Exception ex){

//Log Exception - Cannot close connection

}

}

}This type of method will be used in thousands of places in your application. Don’t put the whole code in every place rather define the above method and use it everywhere like below:

public void dataAccessCode() {

Connection conn = null;

try{

conn = getConnection();

....

} finally{

DBUtil.closeConnection(conn);

}

}3.20. Document all exceptions in the application with javadoc

Make it a practice to javadoc all exceptions which a piece of code may throw at runtime. Also, try to include a possible courses of action, the user should follow in case these exceptions occur.

That’s all I have in my mind for now related to Java exception handling best practices. If you found anything missing or you do not relate to my view on any point, drop me a comment. I will be happy to discuss this.

4. Conclusion

In this Java exception handling tutorial, learn a few important best practices to write robust application code which is error-free as well.

Happy Learning !!

Comments