This article is intended for readers who are curious to know how Java IO operations are mapped at the machine level; and what all things the hardware does all the time when your application is running.

I am assuming that you are familiar with basic IO operations such as reading a file, and writing a file through java IO APIs; because that is out of the scope of this post.

1. Buffer Handling and Kernel vs User Space

The very term “input/output” means nothing more than moving data in and out of buffers.

Buffers, and how buffers are handled, are the basis of all IO. Just keep this in your mind all the time.

Usually, processes perform IO by requesting the operating system that data to be drained from a buffer (write operation) or that a buffer to be filled with data (read operation). That’s the whole summary of IO concepts.

The machinery inside the operating system that performs these transfers can be incredibly complex, but conceptually, it’s very straightforward and we are going to discuss a small part of it in this post.

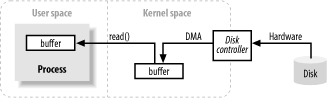

The image above shows a simplified ‘logical’ diagram of how block data moves from an external source, such as a hard disk, to a memory area inside a running process (e.g. RAM).

- First of all, the process requests that its buffer be filled by making the

read()system call. - Read call results in the kernel issuing a command to the disk controller hardware to fetch the data from disk.

- The disk controller writes the data directly into a kernel memory buffer by DMA without further assistance from the main CPU.

- Once the disk controller finishes filling the buffer, the kernel copies the data from the temporary buffer in kernel space to the buffer specified by the process; when it requested the

read()operation.

One thing to notice is that the kernel tries to cache and/or prefetch data, so the data being requested by the process may already be available in kernel space. If so, the data requested by the process is copied out.

If the data isn’t available, the process is suspended while the kernel goes about bringing the data into memory.

2. Virtual Memory

You must have heard of virtual memory multiple times already. Let me put some thoughts on it.

All modern operating systems make use of virtual memory. Virtual memory means that artificial, or virtual, addresses are used in place of physical (hardware RAM) memory addresses.

Virtual memory brings two important advantages:

- More than one virtual address can refer to the same physical memory location.

- A virtual memory space can be larger than the actual hardware memory available.

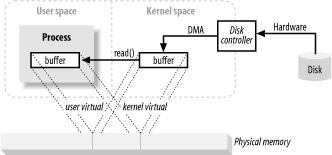

In the previous section, copying from kernel space to the final user buffer must seem like extra work. Why not tell the disk controller to send it directly to the buffer in userspace? Well, it is done using virtual memory and it’s advantage number 1 above.

By mapping a kernel space address to the same physical address as a virtual address in user space, the DMA hardware (which can access only physical memory addresses) can fill a buffer that is simultaneously visible to both the kernel and a user-space process.

This eliminates copies between kernel and userspace but requires the kernel and user buffers to share the same page alignment. Buffers must also be a multiple of the block size used by the disk controller (usually 512-byte disk sectors).

Operating systems divide their memory address spaces into pages, which are fixed-size groups of bytes. These memory pages are always multiples of the disk block size and are usually powers of 2 (which simplifies addressing). Typical memory page sizes are 1,024, 2,048, and 4,096 bytes.

The virtual and physical memory page sizes are always the same.

3. Memory Paging

To support the second advantage of virtual memory (having an addressable space larger than physical memory), it’s necessary to do virtual memory paging (often referred to as swapping).

Memory Paging is a scheme whereby the pages of virtual memory space can be persisted to external disk storage to make room in physical memory for other virtual pages. Essentially, physical memory acts as a cache for a paging area, which is the space on the disk where the content of memory pages is stored when forced out of physical memory.

Aligning memory page sizes as multiples of the disk block size allows the kernel to issue direct commands to the disk controller hardware to write memory pages to disk or reload them when needed.

It turns out that all disk IO is done at the page level. This is the only way data ever moves between disk and physical memory in modern, paged operating systems.

Modern CPUs contain a subsystem known as the Memory Management Unit (MMU). This device logically sits between the CPU and physical memory. MMU contains the mapping information needed to translate virtual addresses to physical memory addresses.

When the CPU references a memory location, the MMU determines which page the location resides in (usually by shifting or masking the bits of the address value) and translates that virtual page number to a physical page number (this is done in hardware and is extremely fast).

4. File/Block Oriented IO

File IO always occurs within the context of a filesystem. A filesystem is a very different thing from a disk. Disks store data in sectors, which are usually 512 bytes each. They are hardware devices that know nothing about the semantics of files. They simply provide a number of slots where data can be stored. In this respect, the sectors of a disk are similar to memory pages; all are of uniform size and are addressable as a large array.

On the other hand, a filesystem is a higher level of abstraction. Filesystems are a particular method of arranging and interpreting data stored on a disk (or some other random-access, block-oriented device). The code you write almost always interacts with a filesystem, not with the disks directly. It is the filesystem that defines the abstractions of file names, paths, files, file attributes, etc.

A filesystem organizes (in hard disk) a sequence of uniformly sized data blocks. Some blocks store meta information such as maps of free blocks, directories, indexes, etc. Other blocks contain actual file data.

The meta-information about individual files describes which blocks contain the file data, where the data ends, when it was last updated, etc.

When a request is made by a user process to read file data, the filesystem implementation determines exactly where on disk that data lives. It then takes action to bring those disk sectors into memory.

Filesystems also have a notion of pages, which may be the same size as a basic memory page or a multiple of it. Typical filesystem page sizes range from 2,048 to 8,192 bytes and will always be a multiple of the basic memory page size.

How a paged filesystem performs IO boils down to the following logical steps:

- Determine which filesystem page(s) (group of disk sectors) the request spans. The file content and/or metadata on disk may be spread across multiple filesystem pages, and those pages may be non-contiguous.

- Allocate enough memory pages in kernel space to hold the identified filesystem pages.

- Establish mappings between those memory pages and the filesystem pages on disk.

- Generate page faults for each of those memory pages.

- The virtual memory system traps the page faults and schedules pageins (i.e. paging-space page ins) to validate those pages by reading their contents from disk.

- Once the pageins have completed, the filesystem breaks down the raw data to extract the requested file content or attribute information.

Note that this filesystem data will be cached like other memory pages. On subsequent IO requests, some or all of the file data may still be present in physical memory and can be reused without rereading from disk.

5. File Locking

File locking is a scheme by which one process can prevent others from accessing a file or restrict how other processes access that file. While the name “file locking” implies locking an entire file (and that is often done), locking is usually available at a finer-grained level.

File regions are usually locked, with granularity down to the byte level. Locks are associated with a particular file, beginning at a specific byte location within that file and running for a specific range of bytes. This is important because it allows many processes to coordinate access to specific areas of a file without impeding other processes working elsewhere in the file.

File locks come in two flavors: shared and exclusive. Multiple shared locks may be in effect for the same file region at the same time. Exclusive locks, on the other hand, demand that no other locks be in effect for the requested region.

6. Streams IO

Not all IO is block-oriented. There is also stream IO, which is modeled on a pipeline. The bytes of an IO stream must be accessed sequentially. TTY (console) devices, printer ports, and network connections are common examples of streams.

Streams are generally, but not necessarily, slower than block devices and are often the source of intermittent input. Most operating systems allow streams to be placed into non-blocking mode, which permits a process to check if the input is available on the stream without getting stuck if none is available at the moment. Such a capability allows a process to handle input as it arrives but perform other functions while the input stream is idle.

A step beyond non-blocking mode is the ability to do readiness selection. This is similar to non-blocking mode (and is often built on top of non-blocking mode), but offloads the checking of whether a stream is ready for the operating system.

The operating system can be told to watch a collection of streams and return an indication to the process of which of those streams are ready. This ability permits a process to multiplex many active streams using common code and a single thread by leveraging the readiness information returned by the operating system.

Stream IO is widely used in network servers to handle large numbers of network connections. Readiness selection is essential for high-volume scaling.

That’s all for this pretty complex topic having loads of technical words :-)

Happy Learning !!

Comments